10. Reformation in the 1500s

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1509 | John Calvin, French reformer, born

|

| 1513 | Leo X becomes Pope (a member of the Medici family, Leo is head of the Catholic Church during the turbulent years 1513-1521)

|

| 1514 | John Knox, Scottish Reformer, born

|

| 1515 | While teaching Romans, Luther realizes faith and justification are the work of God and the way of Salvation

|

| 1517 | Martin Luther nails his 95 Theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany; Zwingli's reform is also underway in Zurich, Switzerland

|

| 1521 | Luther is excommunicated

|

| 1532 | Calvin's conversion

|

| 1534 | Henry VIII declares himself "The supreme head in earth of the Church of England"

|

| 1536 | Erasmus, (Christian) humanist dies

|

| 1536 | William Tyndale strangled and burned at the stake; he was the first to translate the Bible into English from the original languages

|

| 1536 | First edition of Calvin's "Institutes of the Christian Religion"

|

| 1540 | Jesuit order is founded; the Catholic Reformation is under way

|

| 1545 | Council of Trent begins (concludes in 1563)

|

| 1553 | Mary Tudor of England begins her reign; Many Protestants flee Mary's reign; are deeply impacted by reformation on the continent; John Knox is among them

|

| 1558 | Elizabeth I is crowned; exiles from Mary's reign return

|

| 1559 | "Act of Uniformity" makes the 1559 Book of Common Prayer the Church of England standard

|

| 1560 | Jacobus Arminius, Dutch reformer, born

|

| 1572 | John Donne, Anglican minister and poet born

|

| 1572 | Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day, the worst persecution of Huguenots

|

| 1588 | Spanish Armada - motives in part religious, in large part political

|

| 1598 | Edict of Nantes grants Huguenots greater religious freedom

|

Overview

"Reformation" is the term used to describe the revolution that took place in the Western church

in the 16th century. Its greatest leaders were Martin Luther and John Calvin. With far-reaching

political, economic, and social consequences, the Reformation became the basis for the

founding of Protestantism (ie those who "protest"), one of the major branches of Christianity.

The world of the late medieval Roman Catholic Church from which the 16th-century reformers

emerged was a complex one. Over the centuries the church, particularly the papacy, had

become deeply involved (dominant) in Western Europe. The failure of the crusades and the

tragedy of the Black Death changed the fabric of society and weakened the role and credibility

of the Church. The resulting intrigues and political manipulations, combined with ambitious

political rulers who wanted to extend their power and control at the expense of the Church, led

to a weakening of the old order and demands for change. The Age of Exploration (following

Columbus) was also revolutionizing people's thinking. Added to this was the continual threat

from the Muslim world (reverberations from the fall of Constantinople in 1453, and beyond).

To many people (then and since), the Reformation was about getting back to the roots of

Christian faith. "Reformed theology is nothing other than biblical Christianity" (C H Spurgeon).

To some in the 21st Century, the Reformation was all about Calvinism; however this is a narrow

misunderstanding of the broader issues.

Some Influential Christians During This Period

Martin Luther (1483-1546) "Justification by faith"

Luther studied at the University of Erfurt and in 1505 joined a monastic order, becoming an

Augustinian friar. His convent emphasised salvation through prayer, fasting and penance.

Luther was ordained a priest in 1507, began teaching at the University of Wittenberg and in 1512

was made a Doctor of Theology. In 1510 he visited Rome on behalf of a number of Augustinian

monasteries, and was appalled by the corruption he found there.

Luther became increasingly angry about the clergy selling "indulgences" - promised remission

from punishments for sin, either for someone still living, or for one who had died and was

believed to be in purgatory. Indulgences were increasingly being sold across the empire in order

to raise money for the building of Saint Peter's church in Rome. Luther was particularly incensed

at the preaching of a Dominican monk named Johann Tetzel, who travelled around Germany

selling indulgences, declaring that, "as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul

flies out of purgatory".

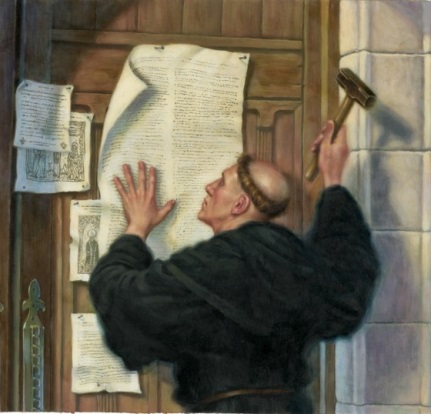

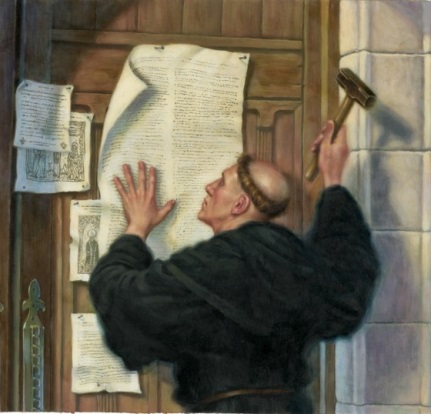

On 31 October 1517, All Saints Day, Luther published his '95 Theses', attacking papal abuses and

the sale of indulgences. Luther had been influenced by Augustine and evangelically minded

friends and had come to believe that Christians are saved through faith and not through their

own efforts. This turned him against many of the major teachings of the Catholic Church. In

1519-20, he wrote a series of pamphlets developing his ideas - 'On Christian Liberty', 'On the

Freedom of a Christian Man', 'To the Christian Nobility' and 'On the Babylonian Captivity of the

Church'. Thanks to the printing press, his 95 Theses (and other writings) spread quickly. Tens of

thousands of copies were distributed throughout Europe.

In January 1521, Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther. He was then summoned to appear at the

Diet of Worms, an assembly of the Holy Roman Empire. He refused to recant (renounce his

ideas) and Emperor Charles V, King of Spain and the most powerful monarch at the time,

declared him an outlaw and a heretic.

Luther went into hiding at Wartburg Castle, where he had been given protection. People living

in the German cities were attracted by the simplicity of his message and the prospects of being

free from foreign political control. In 1522, he returned to Wittenberg and in 1525 married

Katharina von Bora, a former nun, with whom he had six children.

Luther subsequently became involved in the controversy surrounding the Peasants War (1524-

1526), the leaders of which had used Luther's arguments to justify their revolt. He rejected

their demands and upheld the right of the authorities to suppress the revolt, which lost him

many supporters (some became Anabaptists, a branch of the reforming movement - see below).

In 1534, Luther published a complete translation of the bible into German, underlining his belief

that people should be able to read it in their own language.

Luther's influence spread across northern and eastern Europe and his fame made Wittenberg an

intellectual centre. In his final years he wrote against the Jews, the papacy and the

Anabaptists.

"Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason - I do not accept the authority of

popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other - my conscience is captive to

the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is

neither right nor safe. Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen."

Luther before the Diet of Worms, 17 April 1521

Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531)

Swiss theologian, contemporary of Luther, and leader of the early Reformation movement in

Switzerland. Based in Zurich. Denounced the sale of indulgences in 1518.

Zwingli started what is called the Zurich Reformation with sermons that were based on the

Bible. He soon converted the city's council to his points of view. The council pushed the city

into becoming a stronghold of Protestantism and Zurich's lead was followed by Berne and Basle.

Zwingli's '67 Articles' were adopted by Zurich as the city's official doctrine and the city

experienced rapid reform. Preaching and Bible readings - known as "prophesyings" - were made

more frequent; images and relics were frowned on; clerical marriage was allowed; monks and

nuns were encouraged to come out of their isolated existence; monasteries were dissolved and

their wealth was used to fund education and poor relief; pilgrimages were abandoned.

In 1525, Zurich broke with Rome and the Mass became a very simple ceremony using both bread

and wine which represented the body and blood of Christ. Zwingli knew Luther, however they

disagreed on how to interpret the Lord's Supper (Luther preached Consubstantiation). The

church of Zwingli attempted to control moral behaviour and strict supervision became common

in Zurich. The city quickly became a stronghold of Protestantism.

The areas surrounding Zurich feared that it might become too powerful. In 1529, they formed

the Christian Union and joined with the Catholic Austrian monarchy, to defeat the Reformation.

Zwingli preached a religious war against them and two campaigns were launched in 1529 and

1531. Zwingli was killed at the Battle of Keppel (in Zurich) in October 1531. On 9 December

1531 he was replaced by Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575). Less confrontational (Zwingli believed

in using both Bible and sword), more of a pastor, Bullinger wrote and taught extensively (more

than Luther or Calvin, eg he wrote commentaries on almost every book of the Bible) and left a

strong teaching/theological legacy for the reformed churches.

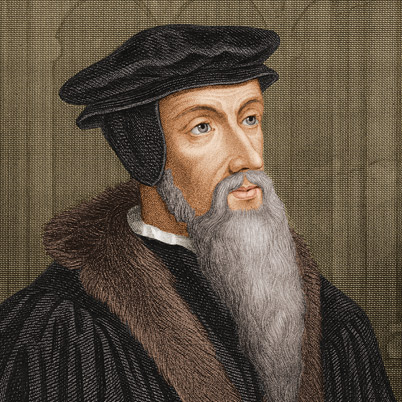

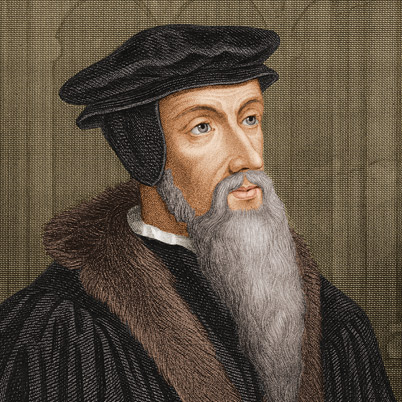

John Calvin (1509-64)

Calvin was a French theologian and reformer. At some point between 1528 and 1533 he

experienced a "sudden conversion" and adopted Protestantism. He fled religious persecution in

France (where "heretics" were regular burned at the stake) and settled in Geneva in 1536. He

instituted a form of Church government in Geneva which has become known as the Presbyterian

Church. He introduced reforms including: congregational singing of the Psalms as part of church

worship; teaching of a catechism and confession of faith to children; and enforcement of a strict

moral discipline in the community by pastors and members of the church.

In 1536 the first edition of Calvin's "Institutes of the Christian Religion" was published. This work

(based on the Apostles' Creed and intended to prove that the reformers were not heretics) was

a systematic explanation of his religious beliefs. Later versions expanded on how the church

should be organised.

In May 1536 Geneva (known for its worldliness) adopted religious reform: monasteries were

dissolved; Mass was abolished; Papal authority was no longer recognised. A struggle then took

place between those who wanted mild versus radical reform. Calvin wanted a city controlled by

the clergy - a theocracy. In 1538, the Libertines won the day and Calvin fled the city and went

to Strasbourg. In September 1541 he returned to Geneva after the Libertines had fallen from

power. Over the next fourteen years he imposed his strict version of liturgy, doctrine, church

organisation and moral behaviour. Many opponents were executed.

Calvin stressed preaching and teaching. Though he liked music, he distrusted its use in religious

services, believing that it distracted people from worship and seeking God; instruments were

banned from churches - though congregational singing was permitted and proved to be both

popular and an effective way of 'spreading' the message. Psalms took the place of hymns.

Calvin was a believer in behaving as God wished. Every sin was made a crime eg no work or

pleasure on Sundays; no extravagance in dress; excommunication meant being banished from the

city. Blasphemy could be punished by death; singing with inappropriate words could be

punished by the culprit's tongue being pierced. The state was subject to the teachings of the

church. Taverns became (for a period) "evangelical refreshment places" where patrons could

drink, accompanied by Bible readings. Meals (in public) were preceded by the saying of grace.

In Calvin's view, Man, who is corrupt, is confronted by the omnipotent and omnipresent God who

before the world began sovereignly predestined some for eternal salvation (the Elect) while the

others would suffer everlasting damnation (the Reprobates). The chosen few were saved by the

operation of divine grace which is irresistible and cannot be earned. The Elect could never fall

from grace. Predestination remains a vital belief in Calvinism.

Geneva became the most influential city in the Protestant movement. It represented the city

where religion had been most truly reformed and changed for the better. John Knox, the

Scottish Protestant leader, called Geneva "the most perfect school of Christ."

Reformed, Congregational, and Presbyterian churches, which continue to look to Calvin as the

chief expositor of their beliefs, have spread throughout the world.

John Knox (1514-1572)

A disciple of Calvin, Knox established Calvinistic Protestantism in Scotland. He left a powerful

political legacy in the form of early Presbyterianism.

From 1542, Scotland was governed by Regent Arran, who passed a law that allowed people to

read the Bible in their own language. He then appointed a Protestant, Thomas Guillame, to

preach throughout Scotland; it was through his preaching that Knox was converted. The biggest

influence on Knox's life was George Wishart. After Wishart's death in 1546, Knox taught the sons

of a number of Protestants who had captured St Andrews Castle; he was invited to become their

minister. In 1547 French warships attacked the castle. Knox was taken prisoner, kept aboard

one of the ships and forced to row in chains with other galley slaves. After 19 months he was set

free and went to England where Archbishop Cranmer was promoting the Reformation. Knox was

appointed as a preacher [in Berwick].

In 1553, Mary I (a Catholic) became Queen of England and Knox left for Europe. He ministered in

Germany and Switzerland (where Calvin was also located). In 1559, he returned to Scotland and

became minister at St Andrews. The following year the first Scottish reformation commenced.

Worship was simplified; evangelism, care of the poor and education were promoted; ordinary

people could read the Bible. Instead of outward forms, worship was now based around reading,

preaching and singing from God's Word. The whole of Scotland was transformed.

Knox prayed: "Give me Scotland or I die". Mary, Queen of Scots, declared that she was more

afraid of the prayers of John Knox than of an army of ten thousand soldiers.

William Tyndale (1495-1536) "The Father of the English Bible"

William Tyndale was ordained to the priesthood in 1521, and soon began to speak of his desire,

which eventually became his life's obsession, to translate the Scriptures into English. It is

reported that, in the course of a dispute with a prominent clergyman who disparaged this

proposal, he said, "If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plow

to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost." The remainder of his life was devoted to

keeping that commitment. Finding that the King, Henry VIII, was firmly set against any English

version of the Scriptures, he fled to Germany (visiting Martin Luther in 1525), and travelled from

city to city, in exile, poverty, persecution, and constant danger. Tyndale did not support church

doctrine, which implied that men earn their salvation by good works and penance. He wrote

eloquently in favour of the view that salvation is a free gift of God, not a response to good works

on the part of the receiver.

Tyndale completed his translation of the New Testament in 1525, and it was printed at Worms

and smuggled into England (of 18,000 copies, only two survive). In 1534, he produced a revised

version, and began work on the Old Testament. In the next two years he completed and

published the Pentateuch (Genesis to Deuteronomy) and Jonah, and translated the books from

Joshua through Second Chronicles, but then he was betrayed by someone he had befriended,

tried for heresy, and put to death. He was burned at the stake (in what is now Belgium), but, as

was often done, the officer strangled him before lighting the fire. His last words were, "Lord,

open the King of England's eyes."

The English Reformation (brief summary)

The English Reformation began in 1534 when King Henry VIII (1509-1547) despaired of obtaining a

male heir on the throne from his wife, Catherine of Aragon. He requested Pope Clement VII to

annul his marriage to Catherine. Since Catherine objected and was, furthermore, aunt of the

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, the Pope hesitated. Impatient with the delay, Henry acted by

repudiating Papal authority and setting up the Anglican Church as the State Church of England

with the King as "Protector and Only Supreme Head of the Church and Clergy of England".

Protestant ideas infiltrated England and Scotland, setting the stage for 150 years of religious

conflict between Catholics and Protestants, and between subsets of Protestants.

When Mary I (1553-1558), daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon and older half-sister to

Elizabeth I, became Queen she restored the Catholic creed and the laws against heresy.

Because of her relentless pursuit of heretics, many of whom were hanged and some 300 burned

at the stake, she has gone down in English history as "Bloody Mary." Large numbers of

Protestants went into exile in Europe. Fortunately her reign was short.

Her sister, Elizabeth I (1558-1603), became head of the Church of England and put down

Catholicism. Elizabeth's reign was generally welcomed by English Protestants. Exiles returned

to England. English was restored as the language of church worship. However she was also

harsh towards many in the Reformation stream, in particular Calvinists.

The (Calvinist) Puritan movement came to notice in England as the result of insistence by

Elizabeth I on the enforcement of uniformity in the dress of the clergy. Because Calvinists

objected to traditional vestments, they were called "Puritans".

This was the beginning of a long confrontation between Puritans and the monarchs, with the

Puritans demanding reform of the Church of England, including doing away with clergy above the

rank of parish priest; abolishing set prayers and elaborate rituals; and reorganizing the Church as

either a hierarchy of councils (Presbyterianism) or a federation of independent parishes

(Congregationalism) free from state control. With the coming of William of Orange (1689), after

the reigns of Charles I, Oliver Cromwell and Charles II, the threat of persecution was lessened by

Parliament; the Toleration Act reduced the grounds for religious dissent and repression.

Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536)

Erasmus was born in Rotterdam. On his parents' death his guardians insisted on his entering a

monastery and in the Augustinian college of Stein near Gouda he spent six years, where he saw

corruption and abuse in the church, and in the ways of the monks. After taking priest's orders

Erasmus went to Paris, where he studied at the College Montaigu. He resided in Paris until 1498,

gaining a livelihood by teaching. Among his pupils was Lord Mountjoy, on whose invitation

Erasmus made his first visit to England in 1498. He lived at Oxford.

In 1516 his annotated New Testament, virtually the first fully Greek New Testament ever

printed, was published. Erasmus sought to introduce a more rational conception of Christian

doctrine. During the Reformation those of the old order blamed him in part for undermining

tradition. The Lutherans, in turn, accused him of cowardice and inconsistency in his teaching.

Erasmus edited a succession of classical and patristic writers, and was engaged in continual

controversies. He emphasized free will over predestination, but rejected Luther's emphasis on

faith alone. He held to transubstantiation and recognised the authority of the Pope. He was a

humanist, but not a secular humanist, ie he believed in God and the Gospel. He sought to

change the Catholic Church from within, rather than breaking away.

Today, Erasmus stands out for his common sense approach to human affairs, his practical

theology, and for opposing abuses in the organised church.

"I wish that the Scriptures might be translated into all languages, so that not only the

Scots and the Irish, but also the Turk and the Saracen might read and understand them. I

long that the farm-labourer might sing them as he follows his plough, the weaver hum

them to the tune of his shuttle, the traveller beguile the weariness of his journey with

their stories." Erasmus

Erasmus

Arminius

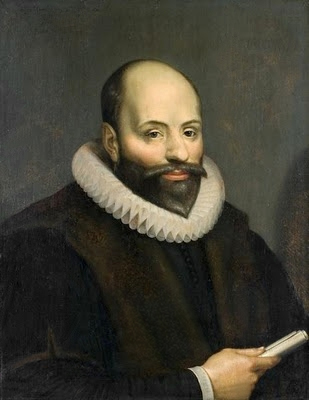

Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609)

Arminius was a Dutch Reformed theologian and professor of theology at the University of Leiden.

He is best known for his departure from Reformed theology. Arminius taught that "preventing"

(or prevenient) grace has been conferred upon all by the Holy Spirit and this grace is "sufficient

for belief, in spite of our sinful corruption, and thus for salvation." Arminius taught that "the

grace sufficient for salvation is conferred on the Elect, and on the Non-elect; that, if they will,

they may believe or not believe, may be saved or not be saved." This means people have a

choice as to whether or not to accept the Gospel; Calvinism was based on God's election alone.

Arminianism remains a central plank in Baptist, Pentecostal, Methodist and Salvation Army

churches.

What were the theological lessons of the Reformation?

The case studies looked at so far are only samples of a movement that impacted an entire

continent over a century. What are the highlights?

The Reformers rejected the authority of the Pope, salvation through good works, indulgences,

the mediation of Mary and the Saints, all but the two sacraments instituted by Christ (Baptism

and the Lord's Supper), the doctrine of transubstantiation, the mass as a sacrifice, purgatory,

prayers for the dead, confessions to a priest, the use of Latin (instead of the vernacular) in

worship, and the forms and paraphernalia that expressed these ideas. Instead, they adopted the

following

- "Sola Fide" (faith alone). We are justified before God by faith alone, not by anything we

do, not by anything the church does for us, and not by faith plus anything else.

- It was recognized by the early Reformers that Sola Fide is not rightly understood until it is

seen as anchored in the broader principle of "Sola Gratia" (grace alone), based on Sola

Christus (Christ alone). The Reformers were calling the church back to the basic teaching

of Scripture (we are "saved by grace through faith and that not of ourselves, it is the gift

of God," Ephesians 2:8).

- Sola Scriptura (Scripture alone). Scripture, as contained in the Bible, is the only true

authority (and final court of appeal) for the Christian in matters of faith, life, conduct

and salvation. The teachings and traditions of the church must be completely

subordinate to the Scriptures.

- Priesthood of all believers. The Scriptures teach that all Christians are a "holy priesthood"

(1 Peter 2:5). We are priests before God through our great high priest Jesus Christ.

("There is one God and one mediator between God and man, the man Christ Jesus," 1

Timothy 2:5.) As believers, we all have direct access to God through Christ, there is no

necessity for an earthly mediator.

- The ultimate aim of the Christian life and witness is Soli Deo Gloria - all for the Glory of

God alone.

Even though the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches fall within Orthodoxy as most

would define it, much of their teaching beyond basic tenets is regarded as inconsistent with the

Gospel by conservative Protestants. In general, evangelical Protestants see the Reformation as a

call back to biblical Christianity.

Controversies

1. Reformation

The Reformation split the church in the West (leading to the Counter-Reformation, or the

"Catholic Reformation"). The theology of the Reformers and their heirs is the heart of historical

evangelicalism. However, just as the Reformers protested the corrupt teaching of the official

church at the time, so today evangelicalism itself is arguably in need of a modern reformation.

2. Anabaptists

The Anabaptist movement started in Europe about 1525. Anabaptists are Christians who believe

in adult baptism, as opposed to the baptizing of infants. Originally used as a derogatory term,

Anabaptist meant "re-baptizer," because some of these believers who had been baptized as

infants were baptized again.

The Anabaptists rejected infant baptism, believing a person can be legitimately baptized only

when they are old enough to give informed consent. They called the act "believer's baptism."

Re-baptism was a crime punishable by death at the time.

Anabaptists believed in the separation of church and state. They preached simple worhip,

removed pictures from churches and emphasised holiness and the power/authority of the Word

of God. They were also pacifist, which led to their estrangement from other Protestant groups.

(What about children who die before they are baptized? Anabaptists believed that infants are

not punishable for sin until they become aware of good and evil and can exercise their own free

will, repent, and accept baptism.)

While Anabaptists were persecuted by Catholics and Protestants alike, belief in adult believer's

baptism remains strong today (eg in Pentecostal, Baptist, Quaker, Brethren and Mennonite

churches.)

3. Arminianism

See above summary. The followers of Arminius (after his death) rejected the Calvinist doctrines

of predestination and election, believing instead that human free will is compatible with God's

sovereignty.

4. "Kingdom of God" or religious dictatorship?

Calvin's model of government in Geneva;

subsequent generations argued for "disestablishment", formal separation of church and

state.

5. Kingdom of God versus political allegiances

- England under Henry VIII, Mary and Elizabeth - the official church moved from

Protestant to Catholic and back several times in line with political developments,

military allegiances and economic interests

- Luther's support of officials during the Peasants Revolt

The Huguenots

The Protestants of France were known as Huguenots. They were part of the Reformation. When

attempts to reform the church were unsuccessful they began to establish their own liturgy and

places of worship which were not under the jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Church.

Despite its early successes, French Protestantism never claimed more than 10% of the population

of France, and there were bitter religious wars which caused great harm and suffering between

1559 and 1598. In 1572 thousands of Huguenots were massacred in the St Bartholomew

massacre in Paris. After the fall of the Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle in 1629, the

Huguenots settled down as citizens of France, hoping to enjoy the civic and religious freedoms

which had been promised them by Henry IV (who had originally been a Protestant) when he

issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598. However, the Roman Catholic Church did everything it could

to undermine the Edict and its guarantees of Protestant freedoms. Life for the Huguenots

became intolerable in the 1680s under Louis XIV who was determined to force them to become

Catholics. In 1685 Louis revoked the Edict of Nantes, and forced many Huguenots into exile.

Those who remained were obliged to become Catholics. However the Protestants of France

maintained their faith in secret, despite vicious persecution, and still exist today.

- Huguenots chose exile in more friendly countries during a long period (probably around

1550-1750) but the main decade of exile was the 1680s when approximately 250,000

people fled France. It was at this time that the word refugee came into the English

language. They went to any country that would accept them, allow them religious

freedom and the chance to work to support themselves and their families. The principal

places of refuge were the Netherlands, England, Germany, Switzerland and Ireland,

although some refugees spread to as far away as Russia, Scandinavia, the American

colonies, and South Africa. Many of their descendants live in Australia.

St Batholomew's Day massacre of Huguenots in Paris

Foxe's Book of Martyrs

The Book of Martyrs, by John Foxe (1517-1587), first published by John Day in 1563, with many

subsequent editions, also by Day, is an English Protestant account of the persecutions of

Protestants, mainly in England, and other groups from former centuries who were seen by Foxe

and others of his contemporaries, such as John Bale, to be forerunners of the Protestant

Reformation through whom the lineage of the church of England could be traced. Though the

work is commonly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, the matters covered are broader; the full

title is Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, touching Matters of the

Church.

Issues Facing Christians During this period

- the Scriptures alone are the sole authority for faith and practice - all tradition must yield

to the authority of the Bible

- salvation comes through Christ alone - all that he has done in his perfect life of

obedience, death on the cross, resurrection from the grave and ascension to at the right

hand of the Father is sufficient for our salvation; there is one Mediator between God and

man = Christ Jesus

- justification is by faith alone - we are right before our heavenly Father only because of

the saving faith that He has worked in us; our good works can never merit right standing

before God

- salvation is by grace alone, ie God's unmerited favor toward us

- dogmatic politicization of the church; ongoing confusion between faith and secular

(Henry VIII, Calvin)

- the challenge of living like Christians while grappling with theological differences (too

many leaders opted for conflict)

Additional Reading

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Halle, HG, Luther: A Biography, Sheldon Press, London, 1981

Lane, T and Osborne, H, Eds, Institutes of the Christian Religion: An Abridged Version, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1986

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973

Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther

on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences

by Dr. Martin Luther (1517)

Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be

discussed at Wittenberg, under the presidency of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of

Arts and of Sacred Theology, and Lecturer in Ordinary on the same at that place. Wherefore he

requests that those who are unable to be present and debate orally with us, may do so by letter.

In the Name our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

- Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life

of believers should be repentance.

- This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance, i.e., confession and

satisfaction, which is administered by the priests.

- Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not

outwardly work divers mortifications of the flesh.

- The penalty [of sin], therefore, continues so long as hatred of self continues; for this is the

true inward repentance, and continues until our entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

- The pope does not intend to remit, and cannot remit any penalties other than those which he

has imposed either by his own authority or by that of the Canons.

- The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by

assenting to God's remission; though, to be sure, he may grant remission in cases reserved to his

judgment. If his right to grant remission in such cases were despised, the guilt would remain

entirely unforgiven.

- God remits guilt to no one whom He does not, at the same time, humble in all things and

bring into subjection to His vicar, the priest.

- The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to them, nothing should

be imposed on the dying.

- Therefore the Holy Spirit in the pope is kind to us, because in his decrees he always makes

exception of the article of death and of necessity.

- Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve

canonical penances for purgatory.

- This changing of the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory is quite evidently one of

the tares that were sown while the bishops slept.

- In former times the canonical penalties were imposed not after, but before absolution, as

tests of true contrition.

- The dying are freed by death from all penalties; they are already dead to canonical rules,

and have a right to be released from them.

- The imperfect health [of soul], that is to say, the imperfect love, of the dying brings with it,

of necessity, great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater is the fear.

- This fear and horror is sufficient of itself alone (to say nothing of other things) to constitute

the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair.

- Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ as do despair, almost-despair, and the assurance

of safety.

- With souls in purgatory it seems necessary that horror should grow less and love increase.

- It seems unproved, either by reason or Scripture, that they are outside the state of merit,

that is to say, of increasing love.

- Again, it seems unproved that they, or at least that all of them, are certain or assured of

their own blessedness, though we may be quite certain of it.

- Therefore by "full remission of all penalties" the pope means not actually "of all," but only of

those imposed by himself.

- Therefore those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope's

indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved;

- Whereas he remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to the canons, they

would have had to pay in this life.

- If it is at all possible to grant to any one the remission of all penalties whatsoever, it is

certain that this remission can be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to the very fewest.

- It must needs be, therefore, that the greater part of the people are deceived by that

indiscriminate and highsounding promise of release from penalty.

- The power which the pope has, in a general way, over purgatory, is just like the power

which any bishop or curate has, in a special way, within his own diocese or parish.

- The pope does well when he grants remission to souls [in purgatory], not by the power of the

keys (which he does not possess), but by way of intercession.

- They preach man who say that so soon as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies

out [of purgatory].

- It is certain that when the penny jingles into the money-box, gain and avarice can be

increased, but the result of the intercession of the Church is in the power of God alone.

- Who knows whether all the souls in purgatory wish to be bought out of it, as in the legend of

Sts. Severinus and Paschal.

- No one is sure that his own contrition is sincere; much less that he has attained full

remission.

- Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences,

i.e., such men are most rare.

- They will be condemned eternally, together with their teachers, who believe themselves

sure of their salvation because they have letters of pardon.

- Men must be on their guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that

inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to Him;

- For these "graces of pardon" concern only the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and

these are appointed by man.

- They preach no Christian doctrine who teach that contrition is not necessary in those who

intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessionalia.

- Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even

without letters of pardon.

- Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has part in all the blessings of Christ and the

Church; and this is granted him by God, even without letters of pardon.

- Nevertheless, the remission and participation [in the blessings of the Church] which are

granted by the pope are in no way to be despised, for they are, as I have said, the declaration of

divine remission.

- It is most difficult, even for the very keenest theologians, at one and the same time to

commend to the people the abundance of pardons and [the need of] true contrition.

- True contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause

them to be hated, or at least, furnish an occasion [for hating them].

- Apostolic pardons are to be preached with caution, lest the people may falsely think them

preferable to other good works of love.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend the buying of pardons to be

compared in any way to works of mercy.

- Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better

work than buying pardons;

- Because love grows by works of love, and man becomes better; but by pardons man does not

grow better, only more free from penalty.

- Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need, and passes him by, and gives

[his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope, but the indignation of God.

- Christians are to be taught that unless they have more than they need, they are bound to

keep back what is necessary for their own families, and by no means to squander it on pardons.

- Christians are to be taught that the buying of pardons is a matter of free will, and not of

commandment.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires,

their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope's pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust

in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God.

- Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he

would rather that St. Peter's church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the

skin, flesh and bones of his sheep.

- Christians are to be taught that it would be the pope's wish, as it is his duty, to give of his

own money to very many of those from whom certain hawkers of pardons cajole money, even

though the church of St. Peter might have to be sold.

- The assurance of salvation by letters of pardon is vain, even though the commissary, nay,

even though the pope himself, were to stake his soul upon it.

- They are enemies of Christ and of the pope, who bid the Word of God be altogether silent in

some Churches, in order that pardons may be preached in others.

- Injury is done the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or a longer time is spent

on pardons than on this Word.

- It must be the intention of the pope that if pardons, which are a very small thing, are

celebrated with one bell, with single processions and ceremonies, then the Gospel, which is the

very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred

ceremonies.

- The "treasures of the Church," out of which the pope. grants indulgences, are not sufficiently

named or known among the people of Christ.

- That they are not temporal treasures is certainly evident, for many of the vendors do not

pour out such treasures so easily, but only gather them.

- Nor are they the merits of Christ and the Saints, for even without the pope, these always

work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outward man.

- St. Lawrence said that the treasures of the Church were the Church's poor, but he spoke

according to the usage of the word in his own time.

- Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by Christ's merit, are that

treasure;

- For it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the

pope is of itself sufficient.

- The true treasure of the Church is the Most Holy Gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

- But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last.

- On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the

last to be first.

- Therefore the treasures of the Gospel are nets with which they formerly were wont to fish

for men of riches.

- The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men.

- The indulgences which the preachers cry as the "greatest graces" are known to be truly such,

in so far as they promote gain.

- Yet they are in truth the very smallest graces compared with the grace of God and the piety

of the Cross.

- Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of apostolic pardons, with all

reverence.

- But still more are they bound to strain all their eyes and attend with all their ears, lest these

men preach their own dreams instead of the commission of the pope.

- He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed!

- But he who guards against the lust and license of the pardon-preachers, let him be blessed!

- The pope justly thunders against those who, by any art, contrive the injury of the traffic in

pardons.

- But much more does he intend to thunder against those who use the pretext of pardons to

contrive the injury of holy love and truth.

- To think the papal pardons so great that they could absolve a man even if he had committed

an impossible sin and violated the Mother of God -- this is madness.

- We say, on the contrary, that the papal pardons are not able to remove the very least of

venial sins, so far as its guilt is concerned.

- It is said that even St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could not bestow greater graces; this is

blasphemy against St. Peter and against the pope.

- We say, on the contrary, that even the present pope, and any pope at all, has greater graces

at his disposal; to wit, the Gospel, powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I. Corinthians

xii.

- To say that the cross, emblazoned with the papal arms, which is set up [by the preachers of

indulgences], is of equal worth with the Cross of Christ, is blasphemy.

- The bishops, curates and theologians who allow such talk to be spread among the people,

will have an account to render.

- This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to

rescue the reverence due to the pope from slander, or even from the shrewd questionings of the

laity.

- To wit: -- "Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire

need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of

miserable money with which to build a Church? The former reasons would be most just; the

latter is most trivial."

- Again: -- "Why are mortuary and anniversary masses for the dead continued, and why does he

not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded on their behalf, since it is

wrong to pray for the redeemed?"

- Again: -- "What is this new piety of God and the pope, that for money they allow a man who

is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God, and do not

rather, because of that pious and beloved soul's own need, free it for pure love's sake?"

- Again: -- "Why are the penitential canons long since in actual fact and through disuse

abrogated and dead, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences, as though they were still alive

and in force?"

- Again: -- "Why does not the pope, whose wealth is to-day greater than the riches of the

richest, build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money

of poor believers?"

- Again: -- "What is it that the pope remits, and what participation does he grant to those

who, by perfect contrition, have a right to full remission and participation?"

- Again: -- "What greater blessing could come to the Church than if the pope were to do a

hundred times a day what he now does once, and bestow on every believer these remissions and

participations?"

- "Since the pope, by his pardons, seeks the salvation of souls rather than money, why does he

suspend the indulgences and pardons granted heretofore, since these have equal efficacy?"

- To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them

by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to

make Christians unhappy.

- If, therefore, pardons were preached according to the spirit and mind of the pope, all these

doubts would be readily resolved; nay, they would not exist.

- Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Peace, peace," and

there is no peace!

- Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Cross, cross," and there is no

cross!

- Christians are to be exhorted that they be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through

penalties, deaths, and hell;

- And thus be confident of entering into heaven rather through many tribulations, than

through the assurance of peace.